Superfluidity: Containers and VMs in the Mobile Network (Part 1)

Among other things, we, at the Superfluidity EU Project (http://superfluidity.eu/), are looking into different deployment models to enable an efficient network resource management in the mobile network. This post describes our findings and focuses on the Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) use case, as well as the technology project, called Kuryr, which enables it.

What is the Superfluidity EU Project about?

First, we will introduce the Superfluidity EU project and its main objectives.

Superfluidity, as used in physics, is “a state in which the matter behaves like a fluid with zero viscosity”. Following the analogy, the Superfluidity project does the same for networks, i.e., it enables the ability to instantiate services on-the-fly anywhere on the network (including core, aggregation and edge), and to shift them to different locations in a transparent way.

For historical reasons current Telco networks are provisioned statistically, however the upcoming network traffic trends require a dynamic way of providing processing capabilities inside the network. These can span across mobile, access networks, core networks and clouds. Cellular networks are still designed for statically connected clients. There are several data and control plane gateways, called GGSN in 3G, and Packet Gateway (P-GW) and Serving Gateway (S-GW), in LTE, which are deployed centrally and in the same way they orchestrate the users’ traffic.

The Superfluidity especially focuses on 5G networks, and tries to go one step further into the virtualization and orchestration of different network elements, including radio and network processing components, such as BBUs, EPCs, P-GW, S-GW, PCRF, MME, load balancers, SDN controllers, and others. These network functions are usually known as Virtual Network Functions (VNFs), and when a few VNFs are chained together for a common purpose they build what is known as Network Service (NS).

The main objective of moving the network functionality, currently running on bare-metal and on proprietary hardware, to virtualized environments is to avoid the rigidness and cost-ineffectivity of this model. The complexity, which emergins from heterogeneous attitude towards traffic and sources, services and needs, as well as access technologies with multi-vendor network components, makes the current model obsolete. This situation requires a significant change, similar to what happened in big datacenters a few years ago with the cloud computing breakthrough.

The Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) use case

Some major international operators and vendors started the ETSI ISG (Industry Specification Group) on Mobile Edge Computing, which advocates for the deployment of virtualized network services at remote access networks, which are placed next to base stations and aggregation points, and run on x86 commodity servers. In other words, its task is to enable services running at the edge of the network, so that services can benefit from higher bandwidth and low latency.

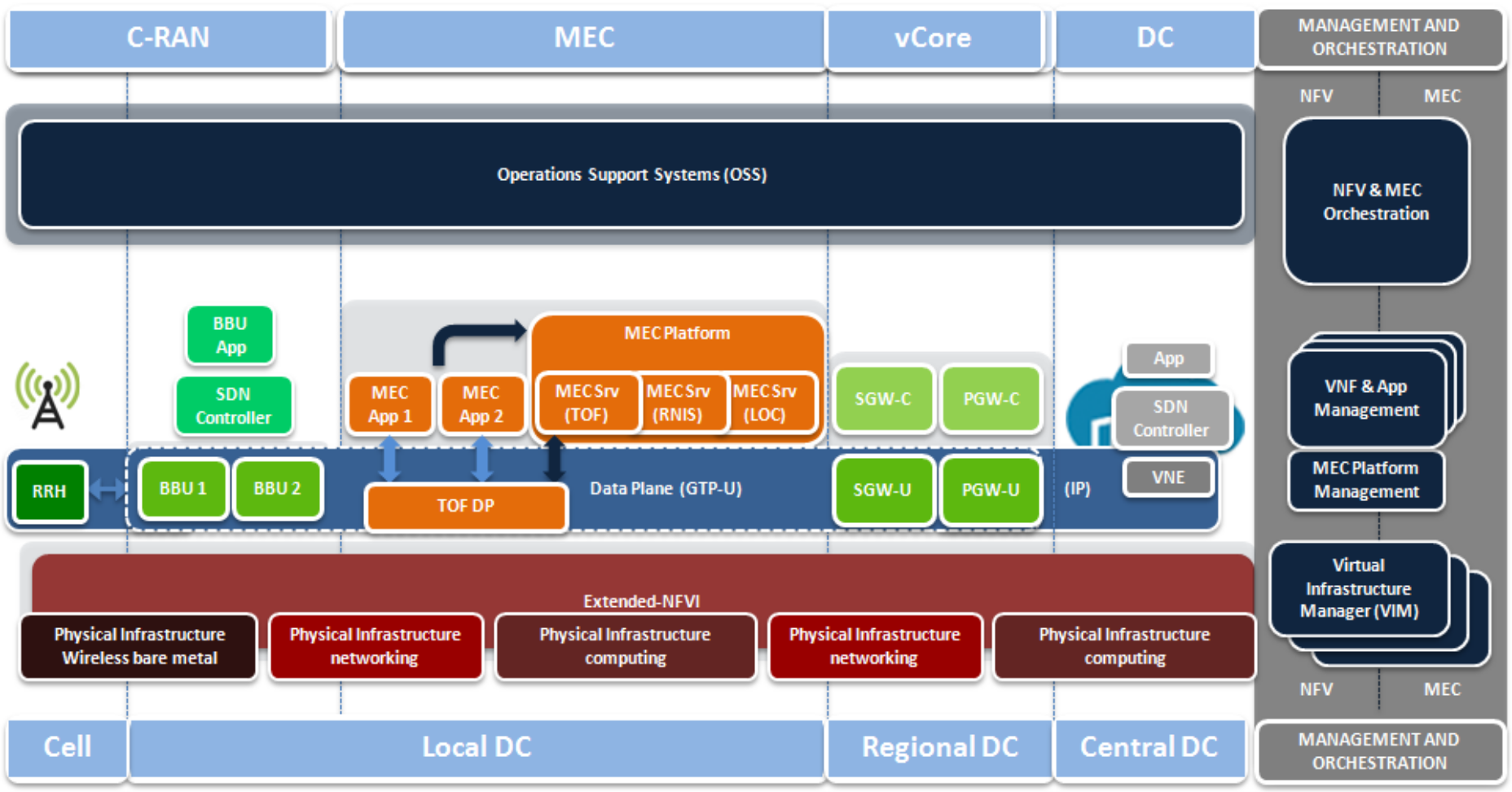

In such a scenario, some network services and applications may be possibly deployed in a specific edge of the network (MEC App and MEC Srv in orange boxes in the above figure). This creates new challenges. On one hand, the network services reaction to current situations (e.g., spikes in the amount of traffic handled by some specific VNFs/NS) needs to be extremely fast. The application lifecycle management, including instantiation, migration, scaling, and so on, needs to be quick enough to provide a good user experience. On the other hand, the amount of available resources at the edge is notably limited when compared to central data centers. Therefore, they must be used efficiently, which results in careful planning of virtualization overheads (time-wise and resource-wise).

Why do we need to react quickly?

To enable the benefits of MEC by merely moving the current functionality from bare metal to Virtual Machines (VMs) is not enough. Mobile networks have some specific requirements, for instance ensuring a certain latency, extremely high network throughput, or constant latency and throughput over time. The Superfluidity project deals with some of the crucial problems, such as long provisioning times, wasteful over-provisioning (to meet a variable demand), or reliance on rigid and cost-ineffective hardware devices.

There are already mechanisms in place that try to provide a more reliable VM performance, such as the NUMA-Aware pinning, huge pages, or the QoS max bandwidth rating to reduce noisy network neighbor effects. In addition, there are other techniques to increase the network throughput of VMs, such as SR-IOV to bypass the hypervisor, or DPDK to use polling instead of interruptions. However, due to high responsiveness requirements expected in 5G deployments, this may still not be enough, as the booting time of the VMs may not be fast enough for certain components, or the virtualization overhead may be prohibitive at some parts of the edge network, where maximizing the resource usage effectiveness is critical due to resource scarceness.

Why do we need containers and VMs?

VMs may not always be a proper approach for all the needs. Instead, other solutions such as the unikernel VMs and containers should be used. In fact, many organizations are looking at Linux containers because of their quick instantiation and great portability, but the containers are also limited to a certain point. It is a well known concern that they are less secure as they have one less isolation layer – i.e., no hypervisor.

It is important to consider where containers are going versus where virtualization already is. Even though there is a high interest in moving more and more functionality to containers over the next years, the priority so far is still set on new applications rather than the legacy ones. Another popular options is to make VMs more efficient in some specific uses. Unikernels, for example, reduce the footprint of VMs to a few MBs (or even KBs), as well as minimize their booting time to make them even faster than containers. This requires to optimize the VMs for a certain use and results in limited flexibility of such a solution. One remarkable example is clickOS. In the future, this will undoubtedly lead to a blend of VMs (both general and specific purpose ones) and containers.

On top of that, there is a belief that containers and virtualization are essentially the same thing, while they are not. Although they have a lot in common, they have some differences, too. They should be seen as complementary, rather than competitive technologies. For example, VMs can be a perfect environment for running containerized workload (it is already fairly common to run Kubernetes or OpenShift on top of OpenStack VMs), providing a more secure environment for running containers, as well as higher flexibility and even improved fault tolerance, and also taking advantage of accelerated application deployment and management through containers. This is commonly referred to as “nested” containers.

How to merge containers and VMS? With KURYR

The problem is not just how to create computational resources, be it VMs or containers, but also how to connect these computational resources among themselves and to the users, in other words, networking. Regarding the VMs in OpenStack, the Neutron project already has a very rich ecosystem of plug-ins and drivers which provide the networking solutions and services, like load-balancing-as-a-service (LBaaS), virtual-private-network-as-a-service (VPNaaS) and firewall-as-a-service (FWaaS).

By contrast, in container networking there is no standard networking API and implementation. So each solution tries to reinvent the wheel – overlapping with other existing solutions. This is especially true in hybrid environments including blends of containers and VMs. As an example, OpenStack Magnum had to introduce abstraction layers for different libnetwork drivers depending on the Container Orchestration Engine (COE).

Knowing these facts, and considering that the Superfluidity project targets quick resource provisioning at 5G deployments, there is a need to further advance in the container networking and its integration in the OpenStack environment. To accomplish this, we have worked on a recent project in OpenStack named Kuryr, which tries to leverage the abstraction and all the hard work previously done in Neutron, and its plug-ins and services, and use that to provide a production grade networking for containers use cases. There are two main objectives:

- Make use of neutron functionality in containers deployments. The Neutron features can be applied directly to containers’ ports, such as security groups or QoS, as well as the upcoming integration of Load Balancing as a Service for Kubernetes services;

- Being able to connect both VMs and Containers in hybrid deployments.

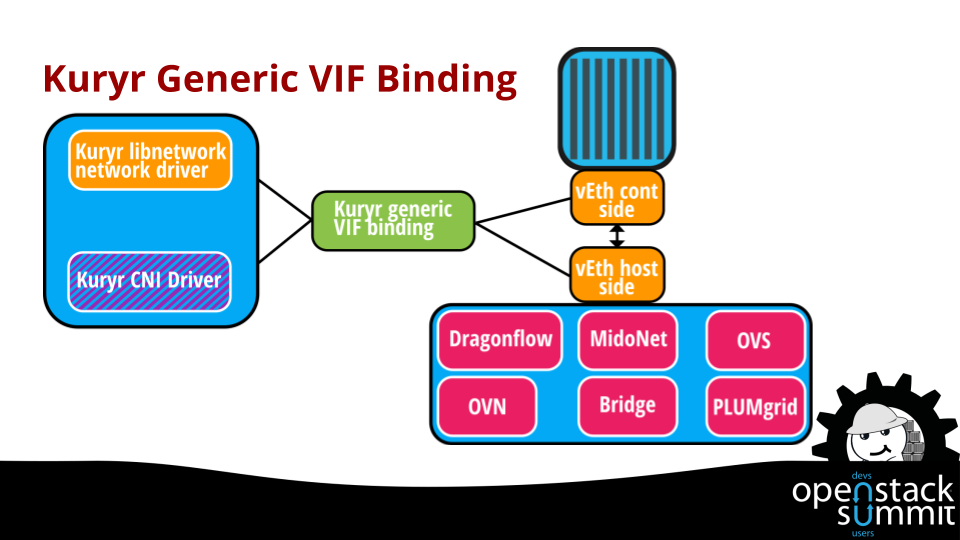

Besides the interaction with the Neutron API, we need to provide binding actions for the containers so that they can be bound to the network. This is one of the common problems for Neutron solutions supporting containers networking as there is a lack of nova port binding infrastructure and no libvirt support. To address this, Kuryr provides a generic VIF binding mechanisms that takes the port types received from container namespace end, and attaches them to the networking solution infrastructure as highlighted in the following figure.

In a nutshell, Kuryr aims to be the “integration bridge” between the two communities, containers and VMs networking, avoiding that each Neutron plug-in or solution need to find and close the gaps independently. Kuryr allows to map the container networking abstraction to the Neutron API, enabling the consumers to choose the vendor and keep one high quality API free of vendor lock-in, which in turn allows to bring container and VM networking together under one API. So all in all, it allows:

- A single community sourced networking whether you run containers, VMs or both

- Leveraging vendor OpenStack support experience in the container space

- A quicker path to Kubernetes & OpenShift for users of Neutron networking

- Ability to transition workloads to containers/microservices at your own pace

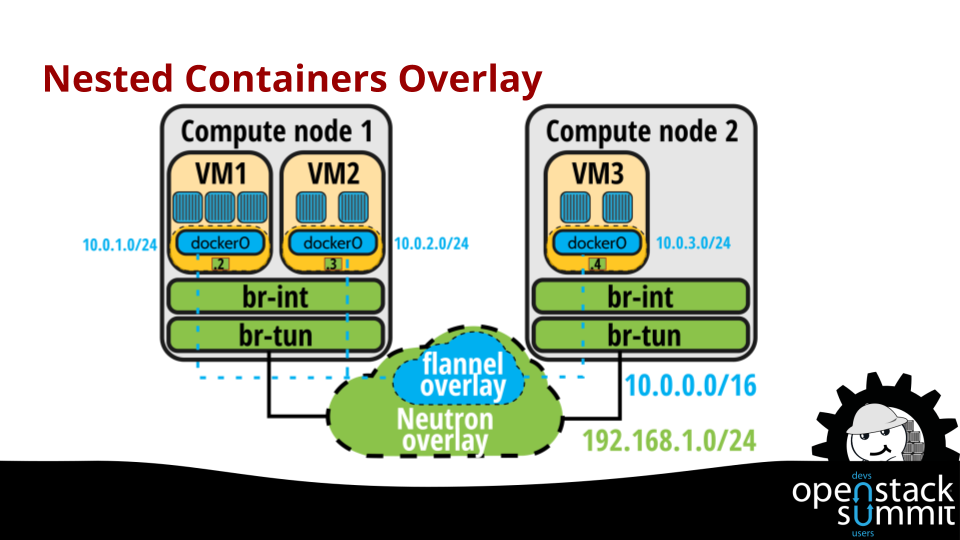

Additionally, Kuryr provides a way to avoid double encapsulation as is the case in current nested deployments, for example when the containers are running inside VMs deployed on OpenStack. As we can see in next figure, when using docker inside the OpenStack VMs, there is a double encapsulation: one for the Neutron overlay network and another one on top of that for the containers network (e.g., flannel overlay). This creates an overhead that needs to be removed for the 5G scenario target by Superfluidity.

Kuryr leverages on the new TrunkPort functionality provided by neutron (also known as VLAN-Aware-VMs) to be able to attach subports that are later bound to the containers inside the VMs, running a shim version of Kuryr to interact with the Neutron server. This enables better isolation between the containers co-located in the same VM, even if they belong to the same subnet as the network traffic will belong to different (local) VLANs.

The continuation (part 2) of this blog post presents two different deployment types enabled by kuryr.